Sensitivity of centennial mass loss projections of the Amundsen basin to the friction law

The Antartic ice sheet represents the world’s largest potential contributor to future sea level rise (SLR). Over 80 % of Antarctica’s grounded ice drains through its fringing ice shelves via ice streams. Because of Archimedes’ principle, the contribution of the ice to sea level is accounted for as soon as it flows through the grounding line (GL), which defines the limit beyond which ice grounded on the bedrock starts floating on the ocean. Therefore, realistic modelling of GL dynamics is crucial to produce trustworthy projections of future SLR. Most of the total motion observed at the surface of ice streams is due to basal slip, which is represented in ice flow models through the use of a friction law, i.e. a mathematical relationship between basal drag and sliding velocities. Because the ice-bed interface is usually out of reach, the formulation of a friction law has been a long-standing problem in glaciology. Various laws intended to describe different physical processes at the roots of basal motion have been developed over the years based on theoretical arguments or derived from laboratory experiments. Unfortunately, the temporal and spatial scales at stake in glaciology make it impossible to validate these different formulations in situ and large-scale ice flow models usually make use of the simplest one, the Weertman law.

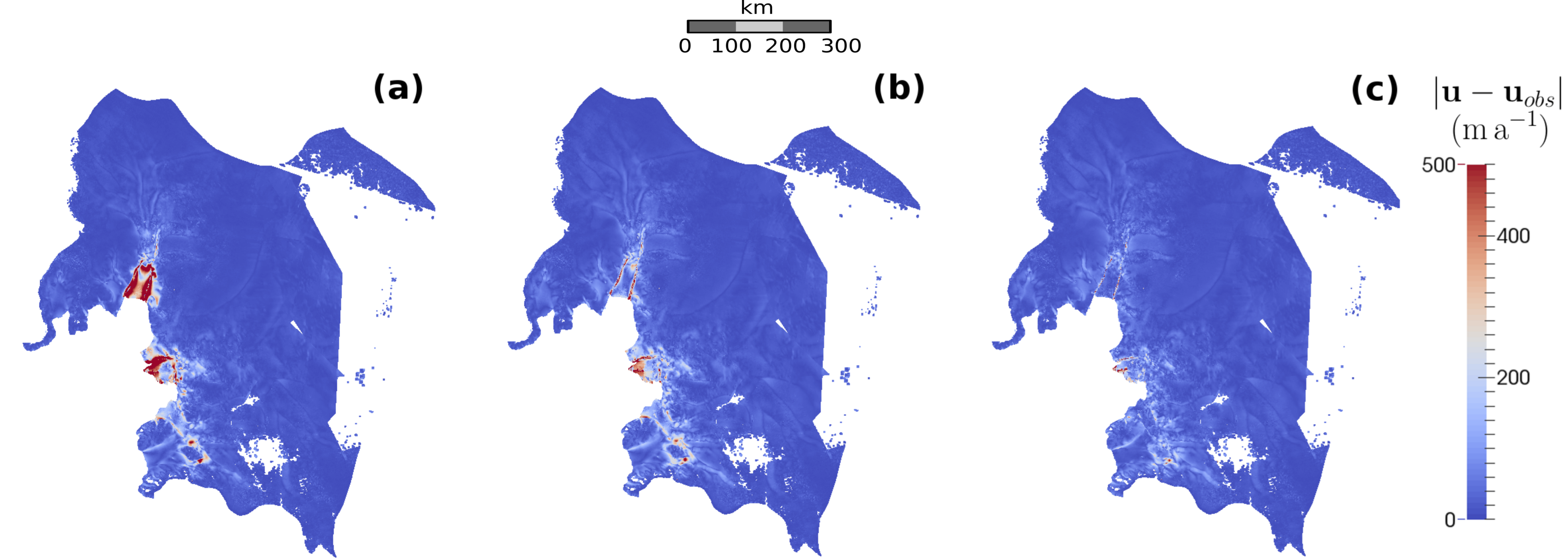

In a previous study (Brondex et al., 2017), we used a synthetic 2D flow line geometry to quantify the sensitivity of the GL dynamics to the choice of the friction law. In this new paper, we extend this work to a real-world application, the Amundsen Sea Embayment, which constitutes the most active drainage basin of Antarctica. The first part of our work involves the construction of model initial states consistent with observations by means of inverse methods. Here, we construct three initial states, which differ by their initial basal shear stress fields and their viscosity fields. It turns out that using observations to infer the basal shear stress field only, while the viscosity field is directly calculated from an available ice temperature field, leads to a poor fit between modelled and observed velocities within and around floating areas. On the contrary, using observations to infer both basal shear stress and viscosity induces a better match between observed and modelled velocities, but the obtained viscosity field may be unrealistic if the relative weight attributed to the two parameters is not suitable (see figure below).

Absolute difference between modelled u and observed uobs velocities (m a−1 ) for the inferred states (a) IRγ,∞ for which only the basal shear stress is inferred, (b) IRγ,100 for which both basal shear stress and viscosity are inferred with intermediate relative weights and (c) IRγ,1 for which both basal shear stress and viscosity are inferred with high relative weights on viscosity.

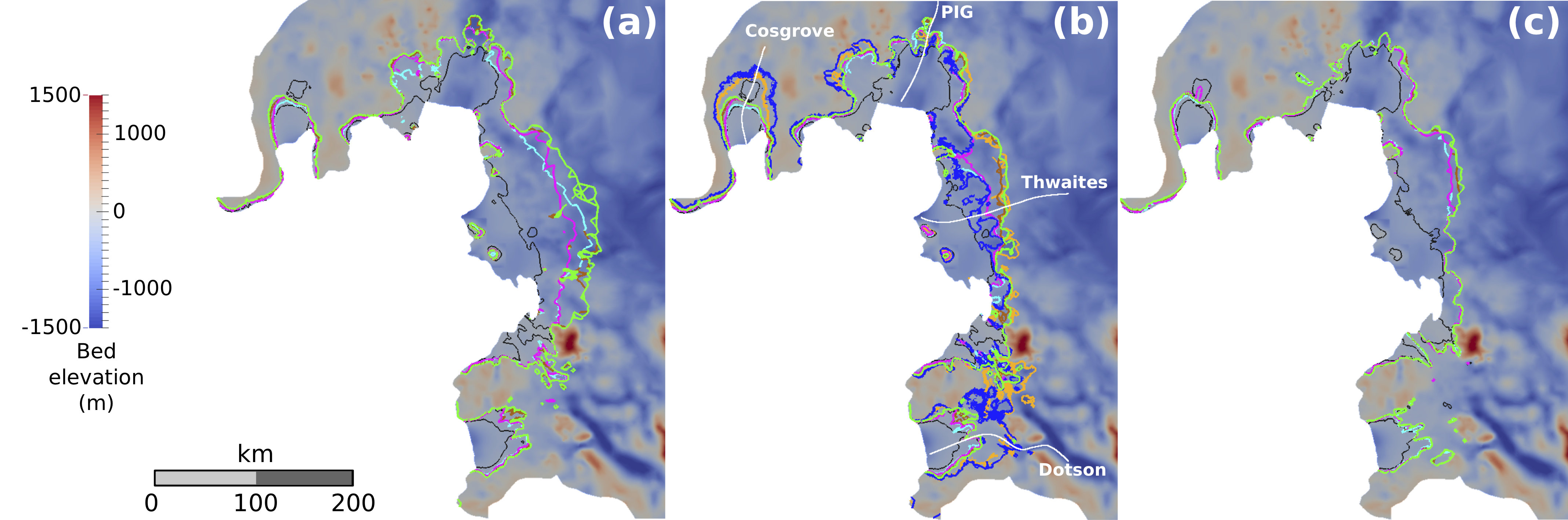

Starting from these three initial states, we perform a 15-year relaxation period with a linear Weertman friction law. Afterwards, the distributions of the friction coefficients of 5 other friction laws – a non-linear Weertman law, a linear Budd law, a non-linear Budd law and a non-linear Schoof law with two different values for the Coulomb friction parameter – which would produced the same fields of basal shear stress as the ones obtained with the linear Weertman law at the end of the relaxation are identified. If these identifications prove to be straightforward for the Weertman and Budd laws, we shed light on specific complications arising with the Schoof law due to the so-called Iken’s bound. Finally, the various combinations initial state/friction law undergo a set of two 105-year prognostic experiments in order to compare their reponses to a synthetic perturbation of oceanic melting rate. Thus, we show that the GL dynamics, and therefore the projections of future SLR, are highly sensitive to the choice of the friction law (see figure below).

Bed elevation (m) and GL positions at the end of the prognostic experiment for the inferred states, (a) IRγ,∞, (b) IRγ,100 and (c) IRγ,1, and the friction laws, linear Weertman (cyan), non-linear Weertman (magenta), Schoof with Cmax = 0.4 (green), Schoof with Cmax = 0.6 (brown), linear Budd (orange, for the inferred state IRγ,100 only) and non-linear Budd (blue, for the inferred state IRγ,100 only). The GL position at t = 0a is reported for each of the three inferred states (solid black lines).

In particular, the commonly used Weertman law systematically underestimates the contribution of the ice sheet to SLR in comparison to the Schoof law, which relies on stronger physical basis since it explicitly takes into account the effect of water pressure at the ice-bed interface. On the other hand, the Budd law not only implies much larger contributions to future SLR but also shows specific GL retreat patterns, which can be attributed to its particular dependence on effective pressure. Although the differences between the results produced with the various laws tend to decrease as more weight is put on viscosity during inversion, they are still significant for the most physically acceptable model state constructed.

The work leading to this publication was supported by the TROIS AS ANR project.

Reference

Brondex, J., F. Gillet-Chaulet, and O. Gagliardini (2018). Sensitivity of centennial mass loss projections of the Amundsen basin to the friction law. The Cryosphere Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-2018-194.